We now start into the finale! Here’s the recap:

25: The Host

24: Searching for the Elephant

23: A Tale of Two Sisters

22: Samaritan Girl

21: Our School

20: 200 Pounds Beauty

19: Taegukgi: The Brotherhood of War

18: Forever the Moment

17: Il Mare

16: Sunny

15: Silmido

14: Oldboy

13: My Love

12: Addicted

11: The Chaser

10: Daytime Drinking

9: Welcome to Dongmakgol

8: Voice of a Murderer

7: My Sassy Girl

6: The King and the Clown

The Finale! The top 5 starts after the jump.

5) Crossing (2008):

Crossing is, by a very large margin, the most depressing movie on my list. That fact alone is one of the reasons that despite a large advertising campaign and international release, the movie still couldn’t break even in the Korean market. Crossing has a lot of competition for the most depressing – especially when considering Voice of a Murderer.

Crossing starts in North Korea. This alone gives it the setting for tragedy and suffering on a scale rivaling the Holocaust labor camps. Yong-soon is a somewhat average North Korean father and husband working for the government in a mine. His young son, Joon, admires Yong-soon because Yong-soon played professional soccer. His wife, however, is growing more and more sick. Due to a disgustingly limited supply of food or medicine, her condition fails to improve. Yong-soon hears that the medicine he needs can’t be bought in the semi-illegal markets in North Korea and the closest place that he can get it is in China. He attempts the dangerous and all-too-common Yalu river crossing, which if caught, means he will spend the rest of his life in “reeducation” while dooming his family to a similar fate.

Yong-soon succeeds in the crossing and starts working at a Chinese lumber mill to raise money for the medicine. However, his plan is cut short when the Chinese authorities raid the lumber mill to arrest the illegal North Koreans. Luckily, he escapes the raid, but with nowhere to go, reunites with the few others that survived. The small group, suddenly distrustful of their employer, decide to seek asylum by storming an embassy after conferring with an organizer trying to politicize North Korean human rights. As a group of twenty-some North Koreans climb the German embassy gates and break barricades, Yong-soon weaves passed the protection and makes it to the embassy while others are arrested around him. After interviewing, Yong-soon is granted asylum in South Korea. But his comfort doesn’t last long as he starts trying to figure out how to get his family to South Korea.

Unknown to Yong-soon is that shortly after he left, his wife dies. With nowhere to go, Joon becomes immediately homeless and a virtual orphan. The neighbors, while sympathetic, are struggling with their own starvation and can only wish Joon luck, unable to offer shelter or food. He wanders around until he finds another kid that offers to help Joon cross the border to China, however Joon isn’t as lucky and is caught. He is then sent to a labor camp, somehow surviving until the strings that his dad set into motion start to work and Joon is bailed out. As a small group of hopeful defectors open their trip to China and then Mongolia, led by a network of people helping North Koreans, Yong-soon starts preparing for his son’s arrival and new life in South Korea.

As stated before, this is the most depressing movie on the list. While in labor camp, we watch pregnant women beaten to kill their “hybrid” Chinese babies and children worked to death. Simple amenities, such as a blanket at night, are denied. While prisoners recite their loyalty to the North Korean leadership, others simply die where they sit. Clearly the labor camp shows there is no interest in letting the prisoners rehabilitate.

Crossing avoids delving too hard into politics. There is never a clear accusation at the North Korean government for creating these conditions, which is a particularly difficult rope to walk. Instead, the criminalization comes from the individuals – the soldiers delighting in the suffering of others. The film’s hesitation to be political actually helps the message because if Crossing were accused of political bias, audiences could subsequently accuse the movie of exaggeration. I’ve read a few books and watched documentaries about defectors that relay consistent stories about the experience. In fact, while I watched the movie hosted by a broker that helps North Koreans escape, several audience members quietly cried during the cruelest scenes. The presenter later told the audience that there were North Korean defectors sitting with us that would attest to the accuracy of the movie, many of them associating with Joon’s experience. What I think is most painful is that the North Korean government, upon learning about the defector’s disappearance, sends all family members to these camps as a deterrence for those considering leaving; a punishment to those who left.

Crossing also walks another fine line by refusing to paint the groups that sneak people out as angelic. This is a much harder choice because the groups that sneak North Koreans out are saving lives. When the defectors come to South Korea, the South Korean government gives financial assistance and education to help the new citizens. Frightfully, the North Korean government has sent assassins through the defector channels to kill those who leave the North, much like Stalin holding a grudge against Trotsky. To counter that, South Korea provides a government agent that watches the new defectors for years to make sure they are honest (while that may be intrusive, I’ve read defectors discussing how helpful the men and women are to shadow for so long, often becoming close friends). In my opinion, those groups that take such dangerous measures to help reunite families are amazing, risking so much to help those yearning for a better life (or simply enough food to survive). Crossing portrays the groups a little grayer, suggesting money as the chief reason that these people operate. Crossing avoids focusing on the goodness of what these people do and instead leaves the door open.

You won’t be happy watching Crossing. Schindler’s List, which seems like a well known and similar story, tries to balance the good and bad (providing a shower for the purchased Jews contrasted against the haphazard sniping of the Nazi). Schindler’s List gives you some moments of relief and happiness, hope for humanity. Crossing doesn’t. Crossing makes you realize how low humanity can go, how cruel we can be, how willing we are to strip dignity and life from other people. The only good thing coming out of Crossing is the realization that some faceless people are trying to help. That may be the only good thing that ever comes out of the North Korea.

4) Memories of Murder (2003):

Korea isn’t hurting for more crime thrillers. Now we are in the top 5 and Memories of Murder is by far the strongest representation of the genre. And like several movies on the list, Memories of Murder is based on a true story. Taking place over 5 years, the movie chronicles attempts by the Korean police to catch the country’s first serial murderer.

The movie opens with a detective at a crime scene. Since Korea has little precedent for murder, there is also little protocol or understanding for how to treat a crime scene. As police casually explore the field where they found the body before taking pictures, kids running around and playing, the detective Doo-man seems unable to convince anyone to be careful. In fact, he can’t stop a tractor that drives over the only evidence they have – footprints left in mud. As important as integrity is to the scene, even Doo-man seems concentrated on the fact that his least favorite reporter is thankfully absent.

Illuminating for how rural the area is, Doo-man’s wife suggests they investigate a mentally handicapped man that followed the victim around the night of the murder (which the wife heard from a friend). While the police try to beat out a confession, they eventually lead the suspect to the woods to dig his own grave. With the threat of death, the man starts recounting details, which the police record as a confession. Doo-man seems comfortable with the confession, convinced they caught the killer and ready to close this case. However, a detective from Seoul, Tae-hoon, is skeptical. After the suspect recants his confession in front of reporters, the police are embarrassed for such quick judgment. Another victim, murdered in the same way, takes Doo-man and Tae-hoon on their search for the country’s first serial killer.

With crime mysteries, the best ones allow the audience to move with the detectives. The best crime mysteries give us access to the same information the detectives have; they don’t use the TV cliffhanger ending where the protagonist yells “It was you!” and then end the scene. We follow the detectives, perhaps we notice something they miss that could solve the crime (it makes us feel smart). In this way, the movies are satisfying because we weren’t deceived by the director – we were deceived by the criminal. On the other side, movies that withhold information or grant us access to something the detectives don’t have are less satisfying because the mystery is maintained by cinematic trickery or police incompetence. I mention this because the next paragraph discusses the ending and I want you to be 100% sure that when I discuss the ending, you won’t care about robbing yourself of an amazing cinematic experience.

In the climatic scene, Doo-man and Tae-hoon believe they have caught the murderer. The slow transformation of Tae-hoon and Doo-man ends with a brilliant role reversal – Tae-hoon, overcome with emotion and anger, holds a gun to the suspect’s head and demands a confession. Doo-man rushes to the two men, bringing the test results from America that would identify the suspect as the killer, allowing a lawful arrest. Tae-hoon pulls the results out, starts reading the document when the worst thing happens: the results are inconclusive. Tae-hoon pulls his gun, disillusioned, and prepares to murder the suspect. He starts firing at the hobbling man, but Doo-man wrestles Tae-hoon back to sanity. Exhausted, the suspect continues walking away as both detectives stand watching.

One of the central themes explored in Memories of Murder is the balance between public safety and constitutional rights. The late 80’s in Korea were times of political discontent as students protested for freedom, eventually toppling the president who attained power through a coup years earlier. Historically, at the time, the police were mainly concerned with putting down violent revolts and arresting student leaders. Clearly it was a time when constitutional rights were hollow. This is why the ending, other than watching the probable killer walk away, is so painful – he’s released by constitutional rights nationally ignored until this exact moment. We know he’s the killer, but the evidence can’t pinpoint him. We watch the suspect leave, unpunished. The audience transforms a little as well. We find ourselves willing to make an exception in this case, willing to look away if Tae-hoon shoots in the general direction. After angrily watching the police beat innocent suspects, we are suddenly supporting the police. We want Tae-hoon to shoot the suspect, maybe just injure him a bit, leave him with something worse than a bloody lip.

The decision to let the suspect go is what is most searing about the movie. Memories of Murder isn't Se7en; it isn’t a movie inspiring hatred for the killer. Instead, what we desire most is justice – we want him to be caught and account for his crimes. We want the two detectives to come back and take another look at the evidence, try to find a way to identify the killer. We want them to work within the legal system, revisit the suspect with a warrant and maybe “accidently” press on his bruises a little. That’s what makes the film interesting and fascinating to watch because it keeps the audience paralyzed. We see the police force beating confessions and grow a disgust for off-the-record justice. That’s how Memories of Murder maintains a desire for legal consequences, until the hopeless scene when we don’t. The reason there is so much back and forth is because I’m still torn between the two…I honestly don’t know, under these circumstances, what I want most. If you’ve read the rest of my reviews, you know a movie has to be pretty good to keep me on the fence.

Memories of Murder is rated number 4 because of entertainment. There are several intense chases and good use of action compared to complicated aesthetic movies that I've mentioned before. Memories of Murder is also the last film that relies purely on entertainment. The next three movies use a lot more art than Memories of Murder, which is ultimately the reason Memories of Murder falls to number 4.

On Amazon: Memories of Murder

3) Joint Security Area (2000):

Continuing with movies involving North Korea, Joint Security Area (JSA) offers great context for the present tensions between North and South Korea. If you’re curious as to why these two countries just can’t see eye to eye, this is the movie that will clue you in. JSA was a blockbuster film that set a record for most tickets sold, a crown passed through the ranks to present day champion The Host.

The film opens with an international incident: A South Korean soldier, injured, flees a North Korean guard post after killing two soldiers and injuring another. The North Koreans claim the South Korean, Seo-hyeok, snuck over in the middle of the night and murdered the North Koreans. Conversely, the South Koreans claim he was kidnapped, but bravely fought off his captors and escaped. In an effort to reduce tensions, an international military investigator, Sophie, is tasked with investigating the incident and discovering the truth of what happened. The film is mostly told through flashbacks as Sophie proceeds with her investigation. It's through these flashbacks that we come to understand the simple political reality.

Chronologically, the series of events starts when Seo-hyeok is on patrol with his company. His company accidently ventures too far from their route and discovers they are in North Korea. They quietly fall back, leaving a urinating Seo-hyeok who tiptoed outside earshot. As Seo-hyeok starts looking for his company, he steps on a landmine triggered to detonate after pressure releases. As he cries, alone, two North Korean soldiers are out for a walk when their puppy leads them to Seo-hyeok. The North Koreans decide to disarm the mine as Seo-hyeok pleads for help. Because of this event, Seo-hyeok realizes the North Koreans aren’t as bloodthirsty as he believed. He opens a dialogue by tying notes to rocks and sending them over, initiating a forbidden correspondence. Since Seo-hyeok feels little camaraderie with his fellow South Korean soldiers, he searches for friendship with the North Koreans a tiny bridge away. The rest of the movie follows the friendship between Seo-hyeok and another South Korean, Sung-shik, with their two North Korean friends.

But of course, since the film opens with Seo-hyeok murdering two North Koreans and injuring another, the story sadly takes a tragic and vain turn. After an alarm goes off that the North is invading, an event occurring days before the killings, Seo-hyeok realizes the danger of continued friendship. He tells Sung-shik that they shouldn’t go over anymore. However, Sung-shik protests that they need to go once more because Seo-hyeok is about to be discharged and they need to celebrate a birthday. As the friends meet for the last time, exchanging gifts and addresses with each other, a superior North Korean officer patrols to the guard post. The officer quickly pulls his gun at Seo-hyeok, causing Seo-hyeok to draw his gun in turn, which spirals into almost everyone suddenly holding a gun at each other. Kyeong-pil, the oldest and wisest North Korean soldier and lone survivor, is the only one who doesn’t arm himself. Kyeong-pil tries to talk everyone down, but struggles to achieve results. As Kyeong-pil continues, the officer cautiously relents, but a radio message forces his hand to quickly reach to his back pocket, prompting the threatened South Koreans to fire. They then turn to the fumbling young North Korean soldier and kill him. Seo-hyeok points his gun at Kyeong-pil, who is standing unarmed and stunned, and tries to shoot him but the pistol jams. Kyeong-pil starts helping the South Koreans, telling them to say they were kidnapped. In the matter of minutes, the friendship between “enemies” is violently concluded, unraveling because old antagonism proved insurmountable.

The greatest strength of this movie is a smaller-scale theme explored in 1999's Peppermint Candy: that the conditions in which we live mold our personalities. For JSA, the characters all become friends despite efforts by both governments to demonize the other. The soldiers overcome these arbitrary differences to form honest and real friendships, aware they are technically enemies but seeing the humanity in each other. But the minute the friendship is tested with the contemporary political situation, the men instantly revert back to their state’s belief. Suddenly, Seo-hyeok is frightened and fearful of his North Korean friends, pulling a gun on them. Seo-hyeok looks like a caged animal, outnumbered and cornered, when in realty he is still among friends. That's why the ending becomes so tragic – a true friendship sacrificed because years of propaganda were too successful.

JSA also needs to be commended for showing a non-political view of the two countries. Remember, North and South Korea are still technically at war. In 2010, North Korea killed about 50 South Koreans (based entirely on news reports from the past 6 months, so there may be more). And for 60 years, South Korea has identified North Korea as the primary threat to their existence. But, JSA suggests, real friendship is possible at an individual level. Despite the easy ability to antagonize North Korea as the perpetual enemy, JSA takes a higher road. JSA wants to show us that the individuals are not the enemies, but as a collective group (such as the government) the problems become pronounced. JSA chooses to fault both countries mutually, solidified by several scenes when the camera flips 180 degrees, showing the South Koreans as upside down.

Sophie, the international investigator, also identifies another problem with how both countries work. Neither wants to acknowledge that a relationship developed between border soldiers (often the most loyal to their country, carefully screened to ensure they won’t defect). Sung-shik even believes that the North Korean kindness reflects training to encourage South Korean defections, as if that is the only reason the North Koreans express cordiality. South Korea wants to maintain a sense of danger, a sense of fear that North Korea can kidnap people at any time, meaning that all South Koreans are equally endangered. So to create a hero, South Korea wants to honor Seo-hyeok who fought against his captors, which is exactly what the U.S. government encourages after flight 93 on September 11th. One of his superiors even says Seo-hyeok should get a medal!

At the same time, the North Koreans want to portray the South Koreans as violent children, crossing the border to kill then running back into the arms of their American big brother. The North Korean message is to always be on guard, never trust the intentions of South Koreans because they could trick you into believing their innocence. So when Seo-hyeok is on the landmine, implicitly, the North Korean government would warn the soldiers to let him stay – perhaps the South Korean is lying, maybe he will kill you when you get close. Over and over the two governments are trying to eliminate a genuine concern for humanity, trying to silence The Good Samaritan. The more fearful a person is of others, the more patriotic they are to the government that protects them. Sophie realizes that neither side is interested in the truth because the situation is the perfect propaganda tool. Each side is content to blame the other for trouble. So they gloss over real progress toward unity and closer cooperation, a focal point for coexistence, to maintain the status quo. If you’re wondering why North Korea continues to threaten war, remember that the threat of war placates the population.

As one of the most successful Korean movies, JSA has a few major problems that prevent me from taking it higher. One of these problems is that the non-Korean actors and actresses are atrocious. In addition to Sophie’s boss laughingly yelling "scheisse!" (shit in German) and Sophie, also from Switzerland, speaking English with an obvious Korean accent, the English dialogue is some of the worst ever written in a movie (and I’ve seen Phantom Menace). Case in point, while a fellow soldier shows Sophie the crime scene, he says this gem: "after the Korean war, the North Korean POW’s crossed this bridge when they were sent back, never to return. That’s why it’s called The Bridge of No Return” in roughly the most scripted and obviously read line of the movie. It’s movies like JSA that make you so thankful that Sunny and The Host didn't just pull people off the street to read the English lines. In this regard, JSA is a zeitgeist to show that Korean filmmakers didn’t expect international attention in 2000, meaning that English speakers didn’t have to be any good because only Koreans would see them.

JSA is an amazing movie with a subversive yet hopeful message. The Korean actors and actresses all do an amazing job, especially Kang-ho Song playing Kyeong-pil. JSA is mostly an entertainment movie, but Chan-wook Park shows some of his artistic flair that becomes more pronounced in his follow up movies Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance and Oldboy. JSA basically gave Park a blank check to make his next film, which is an excellent testament to JSA's quality – that movie studios were so impressed with JSA that he could make whatever he wanted. Even ten years later, JSA is still extremely relevant to understanding contemporary tensions on the Korean peninsula.

On Amazon: J.S.A. - Joint Security Area

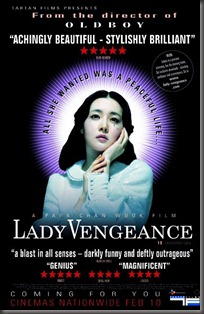

2) Lady Vengeance (2005):

Lady Vengeance is one of my favorite movies of all time. It is the third installment of oft mentioned Chan-wook Park's Revenge Trilogy. It is also the finale, the conclusion, the crescendo and climax for Park's film quest. And wow does Park end with a bang. Lady Vengeance is violent, epic, poetic, beautiful, tragic, passionate and astounding all wrapped into a movie.The film also exemplifies one of the best uses of color to set the mood and pacing, demonstrating Park's precise and meaningful attention to detail (in fact, one version of the film is a complete fade-to-gray).

Lady Vengeance is told non-chronologically, meaning that we see the protagonist, Geum-ja, at several different points in her life. Now, as much as I adore Lady Vengeance, it makes a fairly big mistake early on that prevents it from being the top movie. This mistake is that it introduces too many characters, without context, then forgets about them for a while. When you see them again, you probably have forgotten who they are and what function they serve, a mistake exacerbated by changed clothes and hairstyles. Therefore, another watch through is needed to really understand the full picture. I start with my complaint because you're very first viewing will be slow until the plot picks up about 30 minutes in. Now that that’s over, I can start into my passionate love affair with Lady Vengeance.

So here is the story told chronologically: Geum-ja is a high school student frightened after becoming pregnant. Confused and lonely, she can't face her parents, so she goes to her former teacher Mister Baek. Baek isn't as supportive as he originally seemed, in fact he answers the door naked when 17 year old Geum-ja arrives. Then, as he supports her, Geum-ja learns that Baek kidnaps children to ransom money, believing that rich parents were in the best position to pay him without losing their quality of life. However, “accidently,” the boy that they kidnap is killed by Baek. At this point, since Geum-ja recently delivered her baby, Baek blackmails Geum-ja to take the fall for fear of her child.

After entering jail, she starts doing favors for everyone – so much so that she earns the nickname “kindhearted Geum-ja.” These favors aren't necessarily minor; for example she donates a kidney. But most of her favors possess an aura of seething anger. In another instance, one of the bigger women in prison sexually abuses another inmate, so Geum-ja soaps the floor to cause the abuser to slip and become injured. Once the woman goes to the infirmary, Geum-ja volunteers to bring her food until she recovers. As it turns out, she secretly slips a little bleach into every meal, causing the woman to stay hospitalized for a year before finally dying. As everyone looks at the situation, Geum-ja appears heavenly and kind – she is a Samaritan helping an abusive woman recover (since nobody knew what Geum-ja was actually doing), and Geum-ja keeps the bullied victim safe. In the end, the former victim discovers what Geum-ja did and becomes indebted, promising to help Geum-ja whenever she needs it.

Geum-ja spends thirteen years in jail, performing these favors with the intent of calling in her investment once she leaves prison. Her plot, roughly, is to contact her lost child and then murder Baek for ruining her life. Through all her favors, she has set up a network of people helping her find a job, locate Baek and a willingness to involve themselves with conspiracy to commit murder. As mentioned before, the favors warrant the risky involvement.

The plot takes a brilliant turn about three-quarters through the movie. At this point, Geum-ja has Baek kidnapped and tied to a chair. She is literally pointing a gun at his head, ready to fire and move on with her life. Baek's phone alarm goes off and Geum-ja takes it from him, discovering that he murdered several children and kept keepsakes on his phone. She realizes that he never had a desire to ransom money, but just wanted to kill children. She then sets up this amazing moral dilemma: she contacts the families of all the murdered children to let them know she caught the killer. She shows the families the videos that Baek made of the children’s last moments, then informs them that he made the videos immediately after the kidnapping, using the video tape recordings to prove the children were fine. Calmly, she tells them that he is tied up in the other room and the families can choose what to do: walk away, turn Baek into the police, or get revenge as they see fit.

This twist of the story is the crescendo; a haunting and genius climax for Lady Vengeance. Geum-ja spends the whole film building to the moment when she can kill Baek, but realizing that her revenge deprives the other families from finding justice, she relents. She offers an attempt at peace for the other people. The character decision also adds another twist on the whole image of Geum-ja – is she good? Is she moral? The audience probably has a general philosophy that people devoted and sustained by thirst for revenge are not good people, especially when their chief goal is violent murder. But Geum-ja pauses, not out of a sudden moral dilemma that murder is wrong, but that vengeance heals her while others continue to suffer. She finally starts caring about other people and not using them for a future goal – she stops treating other people as an investment. And while the families debate the moral consequences weighed between lawful and vigilante justice, Geum-ja offers herself as a second sacrifice by a willingness to take the blame for the murder should the police investigate. While watching Lady Vengeance, you will be constantly confronted with an inability to see Geum-ja as a moral heroine or conniving villain.

Lady Vengeance also addresses Christianity in one of cinema’s most creative ways. Considering the moral questions the film raises, it would be easy to attach a Christian lens and try to read religion into a movie that doesn't have it (as an example, Star Wars can be seen through Christian perspectives, but it is my opinion this lens requires weaving together isolated concepts that the film never clearly connects). Lady Vengeance uses Christianity in a few ways that are worth noting. At the start of the film (chronologically near the middle of the story), we see a group of Christians greeting Geum-ja as she leaves prison. We quickly flashback to see Geum-ja converting to Christianity while in prison and giving a sermon that she can summon an internal holy angel through prayer, helping her to become a good person. We see Geum-ja assisting many people, including feeding the abusive woman, as if her Christian conversion has inspired her to witness to fellow prisoners. We see her praying for forgiveness, at one point comforting another woman by saying "prayer is like a scrubbing town. Scrub off all your sins." From many Korean movies I've watched, I've learned a Korean custom that when leaving prison, the newly free prisoner should eat a block of tofu as a symbol of the prisoner’s commitment to never sin again. Geum-ja looks at the tofu held by the priest, knocks it down and tells them to screw off. It seems her conversion was a giant lie. Later, that same priest nearly destroys Geum-ja's plan by telling Baek of the plot and then requesting money – a consequence that nearly leads to Geum-ja's death. Christianity or Christian themes appear explicitly at several junctures, necessitating awareness of the role Christianity plays in Geum-ja’s life.

While in prison flashbacks, many of the prisoners that Geum-ja helps see Geum-ja as holy. In some of the most religious scenes, we see Geum-ja's face illuminated like Saint Mary, possessing the oft-painted halo demonstrating a closeness with God. Some of the posters and promotional materials for Lady Vengeance also play with this image – here are two examples (the movie poster at the end as well):

While the audience sees that Geum-ja isn't quite as good as we first believed, we see the characters looking to her as holy and saintly. Many characters don't see Geum-ja as a bad person – remember, she took the fall for Baek to save her child. She's completely innocent among criminals and doesn't start "sinning" until she kills the abusive woman, which is already morally gray because she does it to protect a weaker victim. If you give the movie a lot of thought, you'll see that her attempts at atonement and salvation are always aimed at her involvement in the kidnapped boy's death – where she didn't even kill him and earnestly believed that kidnapping him would lead to a safe return. One of her first tasks after prison release is to beg forgiveness from the boy’s parents, where she cuts off one of her fingers and threatens to cut more if the family wishes.

One of the other most Christian scenes occurs when all the families are gathered at Geum-ja’s bakery. She serves a cake and offers everyone a slice. As they eat, one of the family members wonders how Geum-ja will return the ransom money to each family. The young woman then slips Geum-ja a piece of paper with her bank account info, requesting a wire transfer. This causes all the other families to start writing down their bank information. Geum-ja looks blank – perhaps the families cared more about the money. There is silence and one of the men casually says “in France, when there's a break in the conversation like this, they say an angel is passing.” The music, the absolute perfect song strummed on a harp, starts and the families all look up and around the room. The camera shows a woman holding her child’s keepsake, taken from Baek. The camera takes the perspective of a spirit – floating around, getting close to faces and hands, unable to completely focus causing some areas of the frame to be blurry like steam on a mirror. While everyone else tries to find their child’s ghost, Geum-ja is staring down at a coffee mug, dressed entirely in black. Someone is smoking and we follow the smoke up to the chandelier with red candles. Geum-ja’s coworker arrives at the bakery, opens the door and the religious experience ends.

As mentioned before, colors play a vital role in Lady Vengeance. Geum-ja, while in jail, doesn't wear any makeup. But after release, she starts wearing a dark pink eye shadow to exemplify the rage building inside her. Her eye shadow slowly fades to red as she grows closer to springing her trap, but at the same time, her face grows paler and drastically highlights her eye shadow. In the end, the color returns to her face as the eye shadow fades to near non-existence. In addition to her makeup, her bedroom is painted red and black – almost like furious and bloodied tiger stripes.

As important as red is, white is by far the paramount color utilized to convey Geum-ja's internal struggle. Coupled with the opening scene where she rejects the white brick of tofu, the constant snow seems torturously beyond reach. At the very end, the color white is finally defined and provides context for how Park uses it throughout the rest of the film. Geum-ja is running through the snow with a package to find her daughter Jenny. Her pseudo-boyfriend is in the background. The narrator says “but she still couldn't find the redemption she so desired.” Geum-ja falls to her knees before her daughter. The same harp from the spirit cake scene reappears. Geum-ja stands up and presents a large white piece of tofu (maybe it’s a white cake, I honestly can’t tell). She looks into her daughter's eyes and says “be white” in English. Jenny raises her eyebrow in confusion. Geum-ja says “live white” in English, “like this,” referring to the tofu block. Jenny dips her finger in and tastes it, smiling before going for another to offer to Geum-ja. Geum-ja stares at it before Jenny eats it and smiles. The daughter looks up at the snow, says “more white” in English, and opens her mouth catching some snow on her tongue. The boyfriend does the same. Geum-ja looks up with tears swelling in her eyes, searching the sky, before she buries her whole face in the tofu. Jenny goes behind Geum-ja and hugs her, the audience left wondering if she found her redemption or not.

The little boy that she kidnapped appears at several scenes in the movie, haunting Geum-ja like a memory. At one point, while Geum-ja and Jenny are sleeping, a rolling marble wakes up Jenny. Sleepily, Jenny looks at the little kid playing and asks “do you speak English?” The child waves his hands, indicating he doesn’t, and she falls back asleep. The narrator comes in and says “for the longest time, Geum-ja wanted to meet with Won-mo and ask for his forgiveness. She’d be very unhappy if she found out he appeared before Jenny.” Near the end, Geum-ja is alone in the bathroom when a marble bounces behind her and rolls to her feet. She picks it up and looks at little Won-mo, on the floor smoking. Geum-ja smiles, then stops and bows her head. As she starts to speak, a hand inserts a ball gag into her mouth and the camera pulls back to see an adult wearing Won-mo’s clothes. This is Won-mo if he lived. He stands over her, towering, and looks down with a sense of pity before turning and walking away. We shift back to Jenny, awakened by Won-mo’s cigarette.

Perhaps what is most memorable about Lady Vengeance is the constant struggle and searching Geum-ja looks for to find atonement, forgiveness and redemption. The addition of religion complicates Park’s revenge finale, making Lady Vengeance the most intellectually mature and explorative of the trilogy. Other critics note the strength of casting a female protagonist, relegating men as weaker before Geum-ja’s wrath. Although this is important and slightly comedic with how Geum-ja treats her boyfriend, Lady Vengeance is much better for the philosophy, religion and acute attention to detail. As stated earlier, to really understand each character you will probably need to watch it twice to pickup who the characters are in the first 30 minutes. Notwithstanding, Park throws amazing artistic talent into an entertaining and fascinating movie.

On Amazon: Lady Vengeance

1) Secret Sunshine (2007):

Now we come to number 1! Secret Sunshine is far less famous than the last 7 movies. Even those familiar with Korean cinema may find Secret Sunshine unknown. This gem barely pulls ahead at the best Korean film of the decade!

The plot is hard to summarize because it mostly revolves around life-changing events and then portrays Sin-ae in her new stage. I’m going to discuss each stage of her life, which encompass a range of scenes:

Arrival: Sin-ae is a young mother arriving in the city of Miryang thankful to be away from people that know her. We’re not too sure what she’s fleeing, but through her conversations, we learn that her husband died in a car accident. She’s shallow and boastful, making business suggestions to people she’s only just met and loudly trying to buy land and build a house. Sin-ae starts renting a little business to teach piano, sends her son to a private school (or maybe it’s an afterschool program) which focuses on public speaking. She also befriends Jong, a local mechanic who always seems an inch away from asking Sin-ae to be his girlfriend. One night, when Sin-ae is out drinking with some other parents who have children in the public speaking school, her son Jun goes missing from home. Sin-ae receives a call to pay the ransom or Jun dies. Sin-ae empties her bank account and drops the money off, but fails to receive her son in return. The police find Jun’s body and arrest the killer.

Suffering: After Jun’s death, she experiences an expected destructive suffering. At Jun’s cremation, she is frozen solid, as if she were really someplace else. Sin-ae loses the joy in her life, the smile she had before, the happiness that helped us like her. Perhaps what is most striking for her at this stage is the physical pain she experiences from the death of Jun. You can see a little of this in the trailer, but her suffering stage is defined by panic attacks she experiences at various times. These panic attacks cause her to clutch her chest, gasping for air, and wailing. I'm not using wailing as a substitute for crying, I really mean she wails.

While Lady Vengeance made nods at Christianity, it is clearly not “Christian.” Secret Sunshine bridges the gap between a Christian film (a character realizes that turning from God is less fulfilling than a closeness with God and then becomes a “true” Christian) and a film that can be better understood with a Christian lens (Lady Vengeance). Miryang is not a Christian film because Sin-ae fails to respond to the Problem of Evil (basically, how can a good and just God allow the innocent to suffer). So while the next stages in her life are Christian or anti-Christian, it is important to see that Secret Sunshine does not take a religious road.

Christian Rebirth: Sin-ae is convinced that she has the strength to register Jun’s death on her own, despite Jong’s offer to help. When she is finally sitting in the chair and questioned, she has another debilitating panic attack. She struggles out of the office and arbitrarily sees a sign to attend a prayer. She stammers into the pew and sits down, listening to the message. As the pastor continues discussing how the Lord releases us from pain with calm praise music playing, Sin-ae pierces the somewhat quiet room with her wailing, gasping for air while clutching her chest. As she cries and screams, the pastor slowly makes his way over, off camera. While the music continues, he places his hand on Sin-ae’s head and walks away, silently. Almost miraculously, Sin-ae calms down. From this point, she joins a Church, prays with Church members, studies the Bible, sings hymns and so on. In other words, she embraces God and His Church.

Christian Death: A few months ago, I wrote an article about haunting scenes from movies you’ve never seen. I made sure to pick scenes from movies that you could get in the U.S., because the scene when Sin-ae’s Christian life perishes is one of the most powerful and painful scenes that film has produced.

Sin-ae makes a magnanimous decision: she will confront Jun’s killer, bring him flowers and let him know that she forgives him. This is what she needs to heal, to move on with her life, to be truly capable of continuing without Jun. Her Church supports her, including traveling with her as Jong drives. She sits down, behind glass, and looks into the man’s eyes. She starts describing God’s love, witnessing to him, how she learned about love through God. The killer interrupts her – he has converted to Christianity while in prison. He prayed for God to forgive him and for the spiritual life of Sin-ae, and her arrival has confirmed that his prayers were answered. He says now that God has forgiven him, he is at peace and will live the rest of his life with God. Sin-ae calmly listens with Jong in the background.

If you weren’t reading this review and saw the movie for the first time, you would agree with Jong when he discusses what happened. It seems like things went great! Two lost souls have come to Christianity, Sin-ae didn’t get emotional and the killer looked ready to live a new life. In the parking lot, Sin-ae collapses. Later, while trying to figure out why she isn’t happy about the chapter closing, we discover what happened: how can she forgive the killer if God already has? How can God give the killer peace but not Sin-ae? Sin-ae is directly affected by the Problem of Evil – how can God help a killer before he helps the innocent sufferer? The first time you see the scene of the killer discussing his new faith, you won't realize how powerfully his words cut Sin-ae. It's only after, once she describes her torment, that we see her faith shattered while listening to the same words she spoke minutes earlier.

Christian Antagonism: Sin-ae succumbs to become an enemy of the Christians that brought her into the Church. At first, she seems to become a sudden atheist, trying to argue that God doesn't exist. She interrupts people praying in Church by loudly banging on the pew. Additionally, she wanders into a large group prayer and starts playing music with lyrics involving lying. The audience is reminded about the times she said that she was close and at peace with God; she believes that the Christian community is lying about the feeling, lying about the inner peace. Implicitly, we can see that she never experienced that peace, that she was basically confused or lying during her discussions about faith. Naturally this must mean the others are lying as well, just needing to be exposed to reality.

She takes her antagonism directly to the woman who introduced her to Church. Across the street from her piano business, there is a little family pharmacy ran by a married couple. The wife tries to convert Sin-ae to Christianity during one of their early meetings then callously (arguable) tries to do it again soon after Jun dies. Sin-ae goes to the pharmacy when the wife isn’t there and starts trying to seduce the husband. Under the pretext that she just needs someone to talk to, she lures the husband to a drive where she starts rubbing his leg. They end up in an empty field where they start kissing and moving toward sex. Sin-ae lays on her back, the camera floating above her face as she stares at the sky. She looks defiant, perhaps even pleased, and starts whispering “can you see?” She is challenging God, showing that she can corrupt and draw people away from Him. Then, ironically, the husband stops. He laments that “I don’t know why I cant. Maybe it’s stress. Or because God’s watching.” He then suggests they made a mistake and should leave. Sin-ae looks angry and defeated.

This scene is an example of how Secret Sunshine maintains agnosticism throughout the entire film. We can see the attempted seduction in two ways: Christian or secular. The Christian aspect is very obvious – God demonstrated that he held authority over her, preventing the husband from becoming aroused since God’s will is to keep the husband faithful to his wife. The secular explanation is just as explanatory. Perhaps the husband, middle aged, suffers from erectile dysfunction. He was reluctant the whole time, perhaps he saw the consequences and chose not to go through with sex. Maybe he and his wife had sex thirty minutes before Sin-ae arrived. Maybe the guilt was too much. The fact that Sin-ae challenges God at that moment could just be a statistical probability; she arbitrarily chose the wrong time and place to approach him. Secret Sunshine stays between these two extremes, never explicit with which it favors, and the audiences’ personal viewpoints will lead the viewer to whichever conclusion he or she prefers.

Another important character in Sin-ae’s life is the killer’s daughter. When we first meet the daughter, she is scorned and in trouble with her father. We come to see the daughter as a distressed girl, easily understandable when we discover her father murders Jun. The daughter appears rarely, but is very important when she does. The daughter becomes a foil for Sin-ae's healing process (a foil exposes character traits). The impetus for Sin-ae deciding to forgive the killer comes when Sin-ae sees the daughter abused by a group of boys. The boys slap her, curse her, and the daughter calmly takes the abuse, looking anywhere and silently pleading for help. Sin-ae is in her car after converting and we expect Sin-ae to take the Christian approach and drive the boys off, rescue the daughter and give her a ride home. But Sin-ae doesn’t. Sin-ae leaves as the daughter stares at her, eyes red from crying as one of the boys slams her head into the wall over and over. The daughter looks hopelessly hopeful – probably wishing it were anyone but Sin-ae that saw her, but still begging for help.

In one of the last scenes, Sin-ae is released from the hospital and decides she needs a haircut. Sin-ae gets two haircuts in the movie: when she arrives to Miryang and hears other women gossiping about her and then this scene. Jong takes Sin-ae to the first salon he finds. Sin-ae sits down before an older woman calls over an employee to cut hair. The employee is, of course, the daughter. Sin-ae looks quietly surprised, but tries to make conversation by asking the daughter how school is and what she's doing. Sin-ae looks cold while hearing what the daughter's life has become: a high school dropout, learning to cut hair while in juvenile detention, parentless and alone in the world. The daughter, quietly responds flatly. After a short time of silence, Sin-ae closes her eyes then opens them with anger and determination. Sin-ae stands up and leaves the salon, mid-cut, and confronts Jong. “Why did you bring me here?” Jong is confused and responds “you wanted a haircut.” Sin-ae counters, “why on earth this one, today of all days?” She looks at the sky, into the distance, scowling at God for teasing her.

A Precarious Conclusion: After the haircut, Sin-ae goes home and starts finishing the haircut on her own. Jong arrives a few minutes later, smiling and offering to hold the mirror. Sin-ae continues cutting and the camera shifts to the dirt. The audience is reminded of what Sin-ae’s husband said about Miryang – that sometimes it's important to walk on real earth. We can see two meanings behind her late husband’s seeming prophecy: Miryang can reduce the powerful to dirt; and Miryang is natural life contrasted against unnatural cities covered in concrete and sidewalks. First, Miryang utterly destroys Sin-ae’s fragile life. While she was already implicitly struggling with the death of her husband and raising a son alone, we also see how strong she is. Sin-ae’s brother is very critical of her late husband for infidelity. This demonstrates that Sin-ae isn’t foreign to tragedy and heartbreak. It's only in Miryang where Sin-ae is crushed by the strength of nature and God. Her previous confident, rich, smug self is reduced to dirt. As Rudyard Kipling wrote in If, “watch the things you gave your life to, broken, And stoop and build 'em up with worn-out tools.” Sin-ae’s haircut signals the rebuilding of her life.

Secondly, Miryang functions closer to what we should see as natural life. Sin-ae leaves Seoul, South Korea’s largest city, because she wants to find something simpler. The audience probably understands this point – we like taking vacations to lakes and forests to help us escape the busyness of city life. But Miryang exposes something that we may forget about nature – as evolution argues, only the strong survive. While none of the regular Miryang citizens exemplify particular strength (excluding, perhaps, the killer’s daughter), we can see Sin-ae through a city weakness. She has become complacent because her city life was too easy, her life in music reflecting privilege and her attempt to buy land and build a new house are symbols of her wealth. In fact, she later admits to lying about how much money she really had – she lies about her wealth to try and gain respect and admiration from the regular Miryang citizens. When she is faced with nature, which doesn't care how rich or elite she is, she crumbles. She falls before the might of nature. It takes Miryang to humble her; she can’t survive in a natural world.

Up until this point, I’ve only briefly mentioned Jong. However, he is one of the most interesting and dynamic characters in the whole movie. Jong functions as Sin-ae’s guardian angel; he’s virtuous, loyal, protective, kind and strong – when we watch Secret Sunshine with a Christian lens, Jong is the heaven-sent angel at Sin-ae’s side. Jong is the third character we meet, arriving in his tow truck to help Sin-ae and Jun get to Miryang when their car breaks down just outside the city. Jong provides support, networking, advice and calls in favors to help Sin-ae get set up with her business. At one point, Sin-ae’s brother goes so far to read Jong as romantically interested in Sin-ae, a claim Jong doesn’t deny or acknowledge. Later, Jong sets up a dinner date at a restaurant, but Sin-ae forgets as she tries to seduce the pharmacist. Subsequently, Sin-ae tries to seduce Jong, who flatly refuses her irrational and dishonest advance. Then Sin-ae storms out, with Jong following apologetically behind.

Jong protects and advises Sin-ae despite her rudeness and demands to be left alone. In that regard, Jong also looks like her conscience. For instance, when Sin-ae prepares to register Jun’s death, Jong keeps trying to go with her. He comically tries to sit down in the same cab before Sin-ae has to literally kick him out. Sin’ae knows that she needs help, but chooses to ignore that part of my mind that recognizes her weakness. It takes Jong to expose how weak Sin-ae has become. Earlier, when Sin-ae’s mother-in-law passionately scorns Sin-ae for failing to protect her family after Jun dies, Jong is the only person who defends Sin-ae. He speaks her words, describes her suffering in ways Sin-ae can’t. Naturally, he is rebuked by the family. And while Sin-ae chops off her own hair, Jong holds the mirror, smiling. We understand that Jong will always be there for Sin-ae, regardless of her behavior. He seems heaven-sent.

But it’s important to remember that Secret Sunshine is agnostic about Christianity, so Jong also isn’t clearly heavenly. Consistent with Korean culture, he faces pressure from his family to marry, which he blows off but then takes a more romantic interest in Sin-ae, obviously aware that he needs to start looking for a wife. He joins the Church that Sin-ae does, volunteering to help with parking. Sin-ae approaches him, dubious of his intentions, and asks if he would swear before God that he has earnest faith. Jong hesitates and the scene ends, suggesting that Jong is trying to share interests and activities with Sin-ae instead of true belief. But because Jong takes so much passive-aggressive abuse, we see his patience as slightly beyond human, slightly better than us.

Secret Sunshine is a movie that stays with you long after you’ve watched it. The movie also requires some reflection, possibly discussion, to really experience the film at it’s strongest point. When I first saw Secret Sunshine, I was far less enthusiastic about the film. It was great and my immediate impression was awe at Do-yeon Jeon, the actress playing Sin-ae. It took a few days before I really analyzed the philosophy behind the film, really gave it some thought. I re-watched it again and gained the full measure of Secret Sunshine’s beauty. If you ever get a chance to see it, I suggest you give it a lot of thought before dismissing it as Sophie’s Choice: full of emotion, but gone after you’ve left the theater. I’m hard-pressed to find any other film, Korean or American, that explores and summarizes two-thousand years of theology with such artistic liberty.

That’s what makes cinema so amazing: a team of artists creating something beautiful and philosophical, willing to tackle hard questions but never arguing to a conclusion. Secret Sunshine guides us, takes us on a journey, explores suffering and redemption, forgiveness and grudges, hope and memory. We never reach a satisfying conclusion, an example to prove one side right and the other wrong. This is cinema, like literature, at it’s peak – suggesting, but not answering; guiding, but not forcing. Secret Sunshine isn't the most exciting, but it is the shining example of filmmaking at the pinnacle of artistic creativity, continuing in the traditions of Citizen Kane, The Godfather, Schindler’s List and all the other films proving that filmmaking is an art, not simply a job.

That concludes my list of the Best Korean Movies of the Decade! Korea doesn't appear to be losing steam in their production of film; from the very few 2010 Korean movies I’ve seen, the quality continues to be remarkably high. And while American cinema is still the undisputed king of worldwide film, Korea cannot be relegated much longer. Please feel free to comment on my choices or discuss my interpretations of any of the movies – like all good art, beauty is in the eye of the beholder.

No comments:

Post a Comment